Inside Polaris’ Pro-Ride Suspension

Progressive action gives the Pro-Ride rider exceptional bump control

According to top engineering executives at Polaris, the company’s snowmobile suspension design team has been thinking outside the skidframe since the turn of the century. We know for certain that Polaris engineers filed a patent for what is now known as the Pro-Ride design in January 2007, more than two years ago. Working under the codename of ‘Blackjack,’ the suspension was shown last summer to a focus group of in-house engineers, marketing types, and some media types — all sworn to secrecy via signed non-disclosure agreements. It was all part of the process required in corporate bureaucracies such as Polaris where General Electric styled management teams hold quarterly business reviews to measure progress.

Fortunately for us snowmobilers, the newest Polaris snowmobile suspension moved through that system to be announced this past January 25th in a marketing haze of internet announcements, media releases, online sneak previews and expensive television exposure centered around ESPN’s created for television Winter X Games.

All new Pro-Ride suspension is the trade secret for the 2010 Polaris Rush.

All new Pro-Ride suspension is the trade secret for the 2010 Polaris Rush.Our preview and test ride came at Daniels Summit in Utah. Our initial impressions are now online history. While we spent much of that ‘First Ride’ review giving you our riding impressions, we left some details until now.

Monoshocking

Pro-Ride’s underseat shock location invites suspension tweaking.

Pro-Ride’s underseat shock location invites suspension tweaking.Give Polaris engineering credit for taking a new look at how to design a snowmobile suspension. The 2010 Polaris Rush enjoys a simple yet convoluted monoshock rear arm concept incorporated into a quite typical parallel rail slide design. The advantages as we see them are two-fold. First, the suspension is progressive in its action. Simply stated it means that you will have to set it super soft for your weight to get it to bottom out. This design absorbs an amazing amount of bump action. The specifications say the rear suspension reacts through 14-inchs of travel. The way it reacts on the trail makes you think it is handling much more than that. Secondly, the main advantage to us riders is the simplicity of setup. In point of fact, the setup is not all that different in concept than many other designs; it just seems so much simpler.

If you make similar adjustments to shocks and springs on a more conventional design, you will end up with a better ride. But the Pro-Ride suspension isn’t hidden between layers of track and mounted where snow and ice make adjustments a serious duty. No, indeed, the Pro-Ride components sit proudly in the open under the seat, inviting a demon tweak every time you make a trailside stop. Two turns of the easy-to-grasp coil spring make changes in 10 to 15 pound weight equivalents. Like a holeshot with full ski lift under full throttle? Lighten your setting. Want ski pressure for control in the corners? Tighten the coil. It is that simple.

Uncoupled

The Pro-Ride front suspension arm and shock set up is conventional.

The Pro-Ride front suspension arm and shock set up is conventional.Unlike many ‘sport’ suspension designs, the Pro-Ride does not couple its articulated rear arm with the standard concept front suspension arm. Both front and rear shocks are on their own. In a coupled design the arms and their shocks borrow effective rates from each other. Polaris engineers felt that while coupling offers some advantages in a conventional design, the actual moment when the two arms transfer rate can cause a serious spike in ride harshness. The Pro-Ride’s progressive rear arm design doesn’t need to borrow rate as it functions progressively through its travel to protect against sharp bottom hits.

You may be thinking that this design concept emulates the old M-10 rear suspension. Remember, though, that those M-10 versions, plush as they were, relied on a falling rate – not a progressive rising rate. If you didn’t get the suspension set just right, you would feel sharp pain as it bottomed. The Pro-Ride gets progressively stiffer in its action. Yes, it can be bottomed out. But you really do need to work at it.

In essence the Pro-Ride works as an articulated rear arm mounted outside the conventional skidframe via a shock absorber arm mounted to the chassis and a bell crank system on the suspension’s rear. This allows linear force to work on a bell crank arrangement to create both vertical and horizontal movement.

Stiff Chassis

Interestingly, while the Pro-Ride rear arm flexes for suspension comfort, the actual chassis needed to be stiffened to assist control and handling response. The engine bay and overall front portion of the Rush chassis features triangulated spars to reduce flexing. You’ll also find this chassis uses a new automotive-type bonding agent (dare we say ‘glue’?) to unite key front pieces. This results in fewer rivets and as much as 12 fewer feet of weld material! The end result is a lighter and straighter chassis.

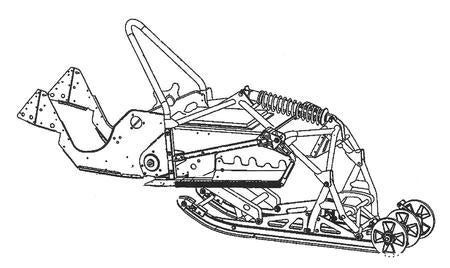

The articulated arm transfers both vertical and horizontal movement.

The articulated arm transfers both vertical and horizontal movement. This track carrier wheels have been added since the Pro-Ride initial concept.

This track carrier wheels have been added since the Pro-Ride initial concept.That glue? Polaris engineers worked for nearly four years to find the right blend of ‘stick ’em’ that not only hold things together in a jouncy snowmobile environment, but also in the rigors of severe -50 Fahrenheit degree ambient temperatures. Polaris feels confident they have found the right blend and reassured us questioners that it would take a couple of seriously powered tow rigs to peel the glued pieces apart. The bottom line is that this methodology of design and construction makes the Rush chassis 60 percent stiffer than other existing Polaris models.

The chassis also features a narrow tunnel top and a three-chambered cooling extrusion that helps with torsion rigidity. As you can tell from full frontal shots of the new Rush, there is also a finned front heat exchanger centered between and ahead of the skis. That all works to keep the Liberty 600 Cleanfire at maximum power.

Looking Forward

Polaris looks to the 2010 Rush and Pro-Ride as its forward-looking statement for snowmobiling. It is a unique design, but we feel that Polaris expects it to be copied. That’s why when we look at this early version of the production Pro-Ride, we see a suspension that can be fine-tuned into a bump-buster for future Polaris models like crossover versions of the Switchback, touring versions and high-performance sports models. We aren’t seeing the Pro-Ride as an answer to deep powder riders, but if the target weight is, indeed, held in check, why not?

However, if you take a peek at the early patent design and compare it to the existing 2010 Rush Pro-Ride system, you’ll see added track carriers and some other pieces that real world testing indicated were needed. Hitting the weight targets may be a challenge. But if this sled rides as well in production as it did in early test rides, we’ll forget a few pounds in favor of inches of travel.

Notice how this early concept drawing differs from the actual production Pro-Ride design.

Notice how this early concept drawing differs from the actual production Pro-Ride design.Going inside the Pro-Ride suspension will be interesting for the Polaris Rush early adopters. Polaris is counting on very good word of mouth to carry this design and its marketing hopes into 2011 when we fully expect to see a larger rollout of Pro-Ride models.

Unlike its unveiling of the Fusion, Polaris has chosen a much safer and saner route. The 2010 Polaris Rush comes with a popular and proven engine. The front suspension is tried and true. The chassis is an enhanced version of a successful design. And the Pro-Ride rear suspension attracts positive buzz with snowmobilers of all mileages. How can Polaris lose?

Related Reading 2010 Polaris Rush Review

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices