Polaris history and heroes

CEO Tiller’s tenure of growth preceded by periods of turmoil and change

As Polaris chief executive Tom Tiller prepares to step down after 10 years of leading the powersports company, it brings to mind a previous Polaris CEO, Allan Hetteen. During Hetteen’s tenure, he faced a 10-year period that paved the way for Polaris’ success into the 21st century.

Hetteen Hoist & Derrick

One of the three founders of Polaris Industries when the company evolved from Hetteen Hoist & Derrick, Allan was the ‘junior’ partner. Nine years younger than brother Edgar, Allan was still in school when Edgar went on his own to establish Hetteen Hoist & Derrick in 1944. The elder Hetteen grew the company through the remainder of the 1940s as his boyhood friend and partner, David Johnson, was away in the US Navy, but sending home a share of his pay to help Edgar establish the new company. It was these three men who turned the operation from builders of agricultural and industrial accessories to a maker of snow machines. In1954, the three renamed the company and set off on a new direction that carries the Polaris name today.

“Hetteen Hoist & Derrick was started to build industrial equipment,” recalls Edgar Hetteen. “It remained that until 1954.”

“One of the reasons we changed the company’s name was because people would come to us and say, ‘We know this Hetteen, but who are Hoist and Derrick?’” Edgar always claimed that was a true story.

Founded in Roseau, Minn., Polaris’ hometown lies near the Minnesota-Canada border. Says Hetteen, “Polaris, that’s the North Star… and we were about as far north as you could get.”

The ‘Industries’ part of the company name was added because, explains Edgar Hetteen “… I learned a name could be too confining. Under the umbrella of Industries you could be anything you wanted.”

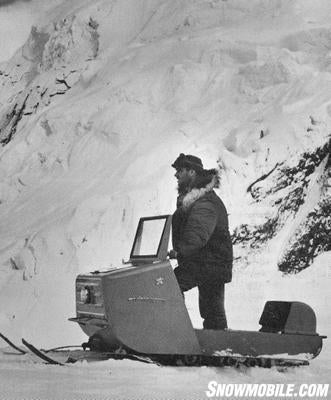

Allan Hetteen stands alongside the second ever Polaris snowmobile.

Allan Hetteen stands alongside the second ever Polaris snowmobile.Snow machines

With the advent of two snow machines built up by David Johnson and Allan Hetteen in their spare time, Edgar saw a future for such snow travelers that could benefit utility companies, the military and outdoorsmen. By the end of the 1950s, Edgar was president of the company but had to answer to a board of directors. In 1959, Edgar conceived of a publicity generating expedition with his company’s snow machines. He would travel along the Yukon River in Alaska and showcase the versatility and durability of Polaris’ Sno-Traveler machines. Engine maker Kohler came on in support since the Polaris-built machines were powered by Kohler single cylinder industrial four-strokes. There were to be write-ups in national and international publications after the expedition completed its run. Edgar felt that this would cement the future of the snowmobile, and that the trip advanced acceptance of the machines by at least five years.

“In 1959,” Edgar would say decades later, “snowmobiling was only five years old. Snowmobiles were not selling. People didn’t trust them.”

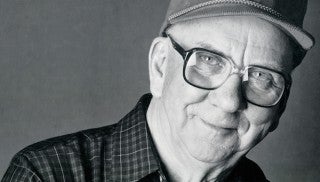

Allan Hetteen at left replaced his older brother, center, after Edgar’s successful expedition to Alaska.

Allan Hetteen at left replaced his older brother, center, after Edgar’s successful expedition to Alaska.Presidents change

Regardless of Edgar’s feelings, the Polaris board saw otherwise and let him know that the president of Polaris Industries should not be running off to Alaska on a foolhardy mission. After 15 years of working to build a solid foundation for the company that once bore his name, Edgar Hetteen had enough of begging bankers and backers for money. He had enough of placating a board of directors who he felt didn’t share his vision. Shortly after he returned from his Alaskan adventure, Edgar Hetteen resigned.

This was the first corporate turmoil to face Allan Hetteen, to whom the Polaris board turned. Only in his mid-30s, Allan had to build off his brother’s adventure and lead Polaris Industries into the new world of snowmobiling. This was the first of three challenges to face the younger Hetteen brother.

He was young and untested. The board prepared to close the doors on the company if the younger Hetteen couldn’t make something of the Sno-Traveler. Recalled co-founder David Johnson: “The heat was on as the board was about ready to lock the doors.”

Allan Hetteen, who was to die near his northern Minnesota home in a tractor accident in 1973, knew that he was being scrutinized. He set to business and established the Polaris snowmachine in western Canada and traveled extensively to promote the product across the snowbelt.

Speaking to a gathering of managers, Allan Hetteen outlined some early Polaris history: “In 1956, we decided to make snowmobiles on a regular commercial basis. In 1958 our Canadian distributor came in with an order for 25 and we were really astonished.

Designed for the 1964 snow seasons the ill-fated Comet simply didn’t work and nearly bankrupt the company.

Designed for the 1964 snow seasons the ill-fated Comet simply didn’t work and nearly bankrupt the company.“We called our machine the Sno-Traveler and it was a real dependable work horse… in 1961 we sold 100 of them to a British geologist team for freighting supplies in the Antarctic.”

Former Polaris chief executive under Textron, Herb Graves, explained the plight of Polaris to dealers at various meetings. “During the first year of operation, six machines were sold. Then followed eight years when acceptance was slow and growth was slow. The world did not beat a path to the door of the small Polaris factory. As late as 1964, only 18,000 units were sold by the entire industry.”

But in 1966, the snowmobile took off. Says Graves: “There was such a fantastic demand that the industry literally couldn’t handle it… and snowmobiling became the fastest growing sport in the country. The next six years were bedlam. Instead of six or seven manufacturers there were 60.”

The second challenge

Having met his first challenge by transitioning the company from Edgar’s presidency to his own, Allan was about to face a challenge that nearly bankrupt Polaris. The total failure of the 1964 Polaris Comet tested his mettle.

This was to be the first major entry into the recreational market. But, as David Johnson recalls, “There were only three things wrong with it: the engine wouldn’t run; the clutch wouldn’t stand up; and the track didn’t go in snow.”

It was jokingly said by Polaris people of the time, “Of the 300 machines built, 800 came back.”

Polaris stood behind the product, but the Comet failure was big enough to bankrupt the company. Allan Hetteen wouldn’t let that happen. He saw to it that vendors got paid, he kept employees working, and he faced down the creditors. He knew that if he could keep the operation going that the next new model, the 1965 Mustang, would be everything that the Comet was not. The Mustang would work and position Polaris for the future.

It was a tough year. Hetteen could have sold off the company for 10 cents on the dollar. He felt the pressure, telling a fellow Polaris executive, “I feel like a man standing alone in a forest with the trees all cut down around him.”

Recreational snowmobiling flourished in the 1960s and the Mustang filled the need for sporty machines.

Recreational snowmobiling flourished in the 1960s and the Mustang filled the need for sporty machines.The final challenge

To his credit, Hetteen’s integrity carried him through to his final challenge as Polaris president.

With snowmobiling on a fast growth pace, he told a gathering, “We could literally sell more machines than we could make without spending a dollar on promotion. But we took a long hard look at the market and decided it was going to be a good one for quite awhile, that the competition would be tougher and that if we wanted to continue to be the leader we had to have the best dealers in the business and establish a strong consumer image.”

Despite the fact that snowmobiling growth was strong, Allan Hetteen recognized that Polaris needed stronger infrastructure and lots more money to compete successfully in the future. In 1968, Hetteen and his board of directors knew that Polaris had to have outside help, either with a partner or through a sale of the company.

He also knew that while he had been successful, he didn’t have the knowledge of big business and the skills necessary to lead a rapid growth. He led a search for a larger corporate partner. Finally, a few options existed. One would put more money in the pockets of the executives and the board, but it would see Polaris absorbed into the larger brand and the factory in Roseau would close. Hetteen couldn’t accept that proposition.

Jim Helgeson, a former Polaris board of director member at that time, recalls one of the biggest things David Johnson, Carl Wahlberg (general manager) and Allan Hetteen were responsible for. They explored the board’s suggestions of which company to sell to. The three went out of the room to decide which offer to accept.

Helgeson remembers: “The board said they would sell out to whoever the three decided on. The three decided on Textron. That was the biggest and best thing that ever happened to Polaris and the Roseau community.”

It was big because Textron brought Polaris in as a wholly-owned subsidiary, yet kept manufacturing operations in Roseau. That meant that instead of jobs being lost, jobs were actually created as under Textron Polaris experienced quick growth and an updating of facilities.

Allan Hetteen stayed on for a while but he would be replaced as president after having seen the company three major transitions in a 10-year period.

Related Reading:

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices