A Future for Lightweight Fun Sleds

Performance first and new ideas second

When we look at the latest new sleds for 2010, we are struck by what’s missing. There is no low-buck, fun to ride sled anymore. Don’t get me wrong, there are some nifty relatively low cost entries, but for the most part they are the “hand-me-downs” of snowmobiling. They are the decontented versions of more popular models. There is the newer chassis, but the powertrain is fan-cooled, carbureted and pull-cord started. The shocks are hydraulic or relatively inexpensive gasbags. And they sell for six grand or more.

We figure that Chris Bell at Premier understands the situation. His 22-horsepower Enforcer 300 snowmobile comes fully loaded for just under US$4,200. His model offers many big sled features in a very attractive package.

But, some how, some where, there must be an alternative between being left with a choice of decontented version of the Big Four’s popular models or opting for a “loaded” entry level model with modest performance, albeit an attractive price tag and design.

Lightweight, Low Cost Concepts

Designed for youthful winter enthusiasts, Ski-Doo’s Freestyle offered a base 300cc powerplant in a new chassis.

Designed for youthful winter enthusiasts, Ski-Doo’s Freestyle offered a base 300cc powerplant in a new chassis.That makes us recall conversations we had with a long ago, iconoclastic snowmobile product manager who argued the merits of a 250cc, 250-pound, 50-horsepower fun sled. There have been attempts over the years and decades to bring ultra-light sleds to the market. Yamaha tried in the late 1980s with its Snoscoot. But the market wasn’t tuned in to a small displacement (79cc) motor scooter derived snow vehicle. The rumor was that Yamaha didn’t really make any money on the scooter as exchange rates took a heavy bite out of the sled’s narrow profit margin. Dealers didn’t understand the product, didn’t see much money being made on the sled, and therefore were not successful convincing their snowmobile customers to buy into the “fun” concept of this ill-fated design.

In the mid-1990s, Ski-Doo attempted to capture the imagination of snowboarders and youthful winter sports enthusiasts with its Freestyle snowmobile. Priced under US$4,000, the Freestyle came with a 300cc motor in a new lightweight chassis. It failed as well, although remnants of the design carried over until this model year in the guise of some utilitarian backcountry models.

Was my iconoclastic product manager friend just blowing smoke? Or, did he have a bigger view of the snowmobile world?

Stymied?

Looking at 2010, we see that the snowmobile companies are stymied. Not so much by imagination, but more by practicalities and market realities. To create the sled my friend envisioned requires thinking outside the market. It’s very chancy with no proven reward. If a sled maker is to “reinvent” the snowmobile, that company needs to have a supportive executive staff with a stomach for potential failure. Polaris has pulled off a minor coup with its new monoshock rear suspension. But on the whole, the biggest risk most likely was internal as we suspect many upper management types were quite willing to let lower level engineers and marketers pay with their jobs if the design failed. The design itself, while interesting, isn’t all that remarkable on the whole. If it doesn’t work — but we agree that it most likely and rightly will be a hit — then Polaris engineers simply move the rear suspension arm back inside the skid frame. After all, that’s kind of what happened with the Polaris multi-position Rider Select steering assembly, which is now virtually nonexistent after a much-ballyhooed introduction a few years back. So, we don’t see Polaris as being the big risk taker for a revolutionary sled design.

Performance First

Taking a risk, Yamaha created a low cost, 79cc snow scooter that is more popular now as a vintage sled than it was when it was first introduced in 1988.

Taking a risk, Yamaha created a low cost, 79cc snow scooter that is more popular now as a vintage sled than it was when it was first introduced in 1988.What are suggesting? It’s a version of what our erstwhile friend suggested. We’ve kept this chap’s idea in the back of our gray matter over the years, shifting it forward from time to time…such as now. Consider that most snowmobilers are actually performance-oriented, not enthusiasts looking to adopt a new idea because it’s simply new and interesting. It must provide a similar level of performance to what their existing sled gives them.

Popular conventional sleds offer a performance to weight ratio of between 2.86 and 3.70 (or just under 4.0). Our power to weight ratio consists of dividing a sled’s claimed horsepower into its claimed or estimated dry weight. We find that Ski-Doo’s 151-hp MXZ Adrenaline 800 PowerTek gives its rider a power to weight ratio of 2.86 (give or take a fraction, after all, we’re word guys not numbers guys). Yamaha’s Nytro RTX SE comes in under 4.0. Based on the performance results of the most popular sports models, we decided that our imaginary new Fun Sled Extreme (FSX) should have a power to weight ratio of 3.25 in order to make it attractive to most snowmobile enthusiasts. If you check our power to weight ratio (PTW) chart, you’ll note that most popular sled models fall within our desired range.

Power To Weight

Of course, we added some models to suggest that despite their lightness of being, they have too little power to give serious enthusiasts the performance level they desire. Example one is the very light fan-cooled Ski-Doo TNT 550. Even though it is a lot of fun on tight trails, it still can’t make up for its 7.48 PTW. Likewise, 22 horsepower may be safe for new riders, but the Premier Enforcer 300 PTW of almost 15 will not cut it. Of course, it’s not designed to be a sport rider’s performance sled anywhere. While the 6.12 PTW we see in the 80-hp Yamaha Phazer RTX would suggest it’s not a performance ride, cross country racers have been quite successful with it against the fan-cooled models from Ski-Doo and others.

We decided, totally arbitrarily, that our imaginary FSX sport sled should have a power to weight ratio of 3.25. To get that in a sled weighing 250 pounds, as suggested by our snowmobile product manager friend, would mean the sled would need to have at least 77 horsepower. Yamaha couldn’t pull that off with its Phazer, which has an 80-hp motor but weighs about the same as Polaris’ Dragon 800. As you can see from the PTW chart, a sled weighing 350 pound requires 108 hp to achieve our arbitrary 3.25 PTW.

New Thinking

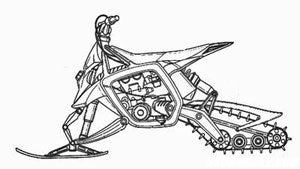

If designed with a powerful enough engine, this Yamaha concept with its a motocross-style rear suspension could provide a power to weight similar to today’s popular sport sleds.

If designed with a powerful enough engine, this Yamaha concept with its a motocross-style rear suspension could provide a power to weight similar to today’s popular sport sleds.Achieving this type of performance in a lightweight sled would require a new piece of paper for all things snowmobiling. It requires fresh thinking not tied into what already exists. And, that may be the biggest barrier to creating a new style performance snowmobile. Existing sled makers would first look at their parts bin. Like Yamaha, they might look at the parts bins of sister product lines — the motor scooter drivetrain for the Snoscoot or the motorcycle parts bin for the 4-stroke, four-cylinder Apex motor. Polaris pulled a motor from its ATV parts bin to power its 4-stroke Frontier model. That’s the kind of thinking that needs to be curtailed. Making something work that you already have on hand isn’t the answer.

No, to get us to where that long-forgotten product manager was suggesting we go requires a fresh sheet of paper. Today we enjoy a head start with lightweight motors and placing the rider forward in a motocrosser riding style, but maybe we need to rethink how that engine sits in the sled and how that drive links to the track. And does the track dictate the suspension or can the track be rethought? How about two 7-inch wide tracks side by side instead of one 15-inch unit? Instead of a monoshock rear arm, what if the entire rear suspension were shorter with more travel arc and extended the sled’s wheelbase? Does Yamaha’s personal snow vehicle design concept match up with some lighter weight, lower powered future sled with a power to weight ratio that matches what we have now?

Challenges Ahead

My friend wasn’t always right. Heck, if he had been, he’d still be in the business today, but he was very good at challenging the status quo. That means that what we have right now may need to change if the sled business is to rebound and thrive in the future. You can always throw more power at heavy conventional designs, but how about throwing unconventional designs at less power, lighter weight and still give us our desired power to weight for performance riding? There are challenges ahead but smart thinking can power tomorrow’s designs. After all, if it weren’t for someone considering slide rails, we’d still be bouncing around on bogie wheels with engines and carburetors sitting in our laps.

Power to Weight Chart:

| Sled | Horsepower | Weight | Power to Weight (Lbs to HP) | Weight to Power (HP to Lbs) |

| Arctic Cat | ||||

| SnoPro 500 | 85 | 440 lbs | 5.18 | 0.32 |

| F8 SnoPro | 150 | 490 lbs | 3.27 | 0.31 |

| Polaris | ||||

| Dragon 800 | 154 | 489 lbs | 3.18 | 0.32 |

| Rush 600 | 125 | 459 lbs | 3.68 | 0.28 |

| Ski-Doo | ||||

| XRS | 151 | 448 lbs | 2.97 | 0.32 |

| MXZ 800 Adrenaline | 151 | 432 lbs | 2.86 | 0.35 |

| TNT 500 | 55 | 411 lbs | 7.48 | 0.14 |

| Yamaha | ||||

| Apex RT | 150 | 568 lbs | 3.79 | 0.27 |

| Nytro RTX SE | 135 | 529 lbs | 3.92 | 0.26 |

| Phaser RTX | 80 | 489 lbs | 6.12 | 0.17 |

| Enforcer | ||||

| Enforcer 300 | 22 | 328 lbs | 14.91 | 0.07 |

| Extreme Fun Sled | ||||

| FX | 100 | 325 lbs | 3.24 | |

| FX Heavy | 108 | 350 lbs | 3.25 | |

| FX Light | 77 | 250 lbs | 3.25 | |

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices