Innovation Trends in Snowmobiling

Are we entering a new age of snowmobile innovation?

Some innovations seem obvious once they hit the marketplace. After all, Ski-Doo’s rider-forward REV platform made immense sense, once we saw and rode it. Pre-REV snowmobilers simulated rider-forward positioning as they pulled themselves forward on the saddle to get more ski pressure and improved balance for cornering. Having the sled’s design get you there was an “ahh-ha” moment. That rider-forward breakthrough in 2002 totally changed the way we ride sleds.

That innovation may have been the most significant in sled history since Arctic Cat created its slide rail rear suspension. A profound advance over bogie wheel design, the Cat’s slide rail created a change in rider comfort and led to a flurry of advances in suspension design as well as some other similar and patent-challenging slide rail concepts. In today’s world of snowmobiling, bogies are relegated to vintage riders as slide rail suspensions rule.

Ski-Doo set a trend with its rider-forward REV chassis and created variants that could be used in trail sleds and even as wide-body utility ones.

Ski-Doo set a trend with its rider-forward REV chassis and created variants that could be used in trail sleds and even as wide-body utility ones.In the mid-1970s ski suspensions saw a major technology shift when Polaris added independent front trailing arm suspensions to its RXL Sno Pro sleds and slammed the door on its competitors. That innovative action moved from track to trail when Polaris unveiled its popular TX-L Indy 340 and used it to win more prestigious long distance terrain races like the legendary Winnipeg-To-St. Paul I-500 than all other snowmobile makers combined.

Yamaha Unveils Electronic Power Steering

Of course, the switch from leaf sprung skis to independent front designs was not automatically in favor of the Polaris-style IFS. Yamaha opted for telescopic struts, importing engineering from its motorcycle side. Ski-Doo tried various designs, including a long travel telescopic system that it retains on 2016 Tundra and Skandic models. Arctic Cat went another direction, choosing A-arms that became its Arctic Wishbone Suspension (AWS). Virtually all modern snowmobiles feature a ride-forward platform, slide rail rear suspension and an A-arm front suspension.

Modern Yamaha snowmobiles feature A-arm front suspensions even though it was first to market telescopic strut suspensions, which Ski-Doo still uses on select utility models like its Tundra and Skandic.

Modern Yamaha snowmobiles feature A-arm front suspensions even though it was first to market telescopic strut suspensions, which Ski-Doo still uses on select utility models like its Tundra and Skandic.Innovation can start slowly but once it’s proven it can become a staple. That may be where we are today as we look to several ideas that have yet to go mainstream.

Yamaha needed to convince riders that its sleds could be light and nimble, so it innovated by adding electronic power steering (EPS) to its Yamaha-built Apex, Vector and Venture models. Objections to heavy steering effort dissipated. But, since EPS had gained a good following with ATV riders when Yamaha, Honda and Polaris added it as a feature, its addition to Yamaha snowmobiles wasn’t much of a gamble. Still, only Yamaha offers EPS on sleds even though we can think of a few non-Yamahas that could be helped with a steering boost.

Another innovation that seems logical and may be ready for a breakthrough could be anti-lock braking. Hayes TrailTrac is a performance electronic braking system that was developed for snowmobiles and introduced at HayDays in 2013. While a solid idea, TrailTrac has yet to find a consistent niche as a standalone add-on. What could put an upward spike in interest would be inclusion of the system as standard equipment on a sled maker’s high performance model. That’s not such a far-fetched idea as Hayes currently supplies hydraulic brake systems to Arctic Cat, Yamaha and Polaris – just not the TrailTrac system. The TrailTrac would add cost, but every snowmobile manufacturer offers uniquely packaged “special editions” as early season premiums.

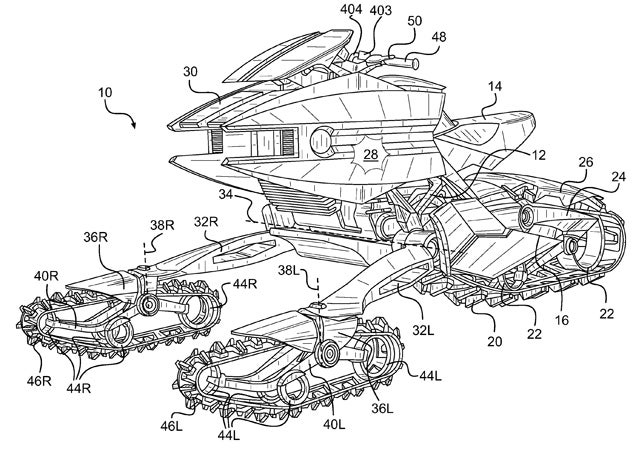

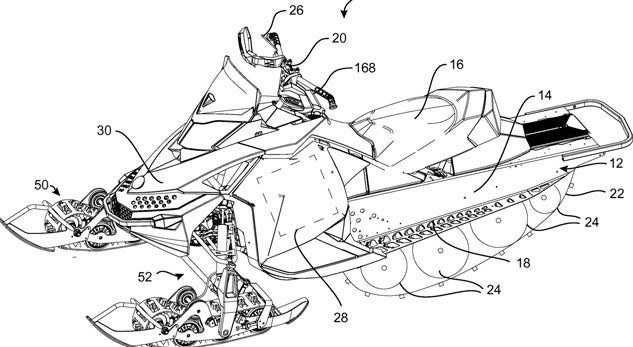

This “Mad Max” sled is actually a 2008 BRP conceptual drawing of how a ski-track assembly might be used as part of the sled’s overall braking system and complement traditional rear track braking.

This “Mad Max” sled is actually a 2008 BRP conceptual drawing of how a ski-track assembly might be used as part of the sled’s overall braking system and complement traditional rear track braking.Of course, it could be that the Hayes system, which retails for about US$1000, could be made redundant if some clever new ideas about adding braking capability to snowmobile skis break cover and become reality. What, you say? How’s that?

Ideas for the Future of Snowmobiling

Let’s consider for a moment that few of us saw an adjustable ski as a reality. On reflection and examination of the Ski-Doo design, the BRP engineering crew scores a coup and creates a major ‘Ah Ha! Moment. The concept is clever enough, but for any small boat sailor who sails with a daggerboard or centerboard, he’s familiar with the idea of a dagger moving up and down in a casing. His response would be, “Of course, why didn’t I think of that?”

While the Ski-Doo ski may be unproven as of now, but if proven over time, look for imitations coming on stream. Don’t think that the idea of adding grip via an adjustable ski will be the only unique front-end alteration to future snowmobiles.

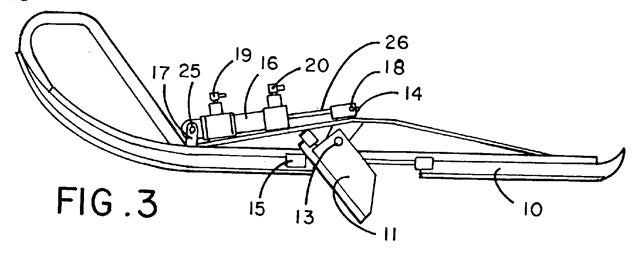

In 1997 Gregory Hoffman filed a patent for a snowmobile braking system that hydraulically extended blades from the center of the skis for braking.

In 1997 Gregory Hoffman filed a patent for a snowmobile braking system that hydraulically extended blades from the center of the skis for braking.How about adding a braking device to the ski and adding three points of stopping power instead of just one at the track? In 1997 Gregory Hoffman filed a patent for a snowmobile braking system that hydraulically extended blades from the center of the skis for braking. Of course, the late 1990s patent centered around the continued use of leaf sprung skis and not modern IFS controlled skis.

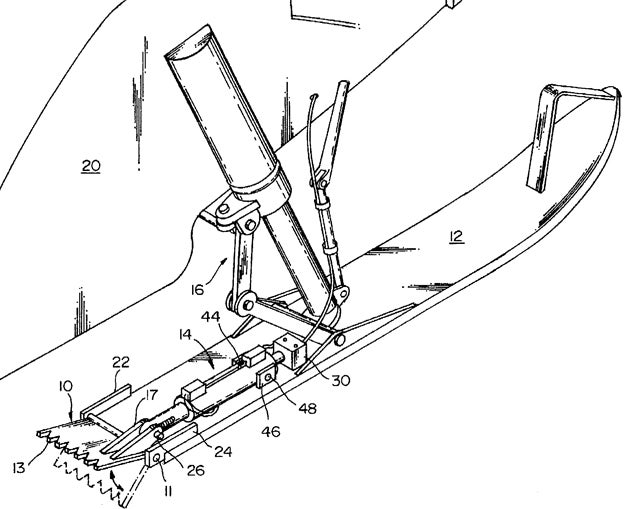

Two years earlier, Robert L. Martin filed for a snowmobile braking system that lowered a braking claw at the trailing end of the ski. The rider could activate the claw device, which would pivot downward and dig into the snow. The claws would be activated in unison to provide balanced braking while allowing the rider to still maintain steering control. Based on the drawing supplied with the patent application, this design appears intended for a telescopic strut suspended ski.

Robert L. Martin’s snowmobile braking concept lowered a braking claw at the trailing end of the ski.

Robert L. Martin’s snowmobile braking concept lowered a braking claw at the trailing end of the ski.There have been myriad designs for adding braking power to a snowmobile. Based on past innovation, one concept that we take seriously is one filed December 2014 and published in April of this year. The patent, filed on behalf of Bombardier Recreational Products, is for a “Front Track Assembly for a Snowmobile.”

The idea of using the skis as a part of the braking equation is not new, but this idea put forth by BRP engineers uses the ski to house a free-rotating track moving around wheels that can be braked.

The idea of using the skis as a part of the braking equation is not new, but this idea put forth by BRP engineers uses the ski to house a free-rotating track moving around wheels that can be braked.This is more outside the box thinking from the engineering staff based at Ski-Doo’s “Why Not?” think tank in Valcourt. This design is a continuation of a previous application that was filed in 2012.

Personal Snow Vehicle Concepts

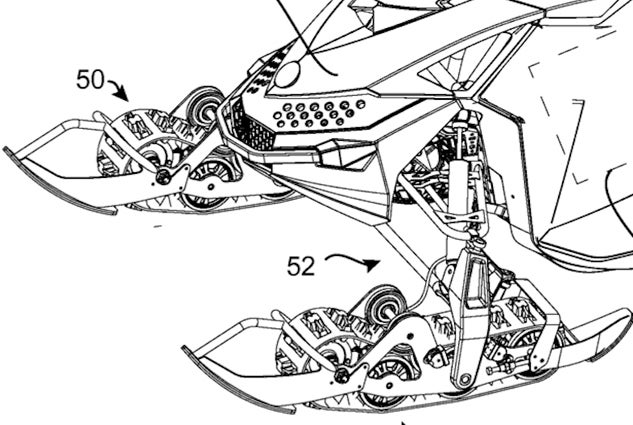

The idea is to create a tracked ski with a front track assembly that would feature a pivotable front ski element connected to the track that allows steering as well as a braking system.

The basic idea is to create added braking power by making the skis a part of the braking system. The applicants note “…during braking, a portion of the weight of the snowmobile is transferred from the rear track to the front skis. However, the front skis do not assist in braking, despite bearing an increased proportion of the weight of the snowmobile, because they are designed to float above the snow and generate as little friction with the snow as possible. It may be desirable in some snowmobiles to provide braking at the front of the snowmobile in view of this weight transfer.”

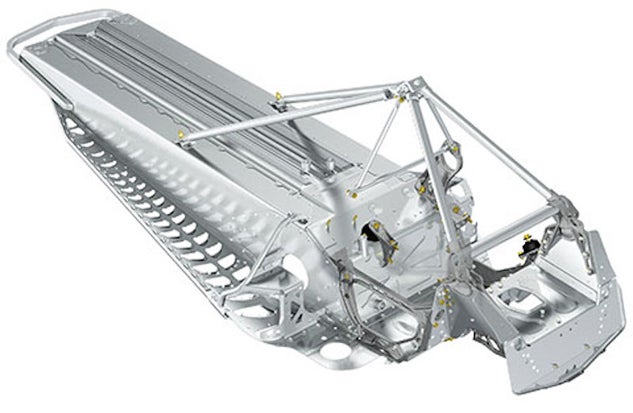

This close-up view of BRP’s “tracked” ski reveals a front track assembly that could feature a pivotable front ski element connected to the track that allows steering as well as a braking system.

This close-up view of BRP’s “tracked” ski reveals a front track assembly that could feature a pivotable front ski element connected to the track that allows steering as well as a braking system.In essence the ski houses a free-rotating track moving around wheels that can be braked. There doesn’t appear to be any power takeoff derived from the engine to drive the wheels, merely a system that responds like a drum brake.

The idea of using the skis as a part of the braking equation is not new, but this idea put forth by BRP engineers is different than previous ideas.

While this brake system may never see production, it does indicate a willingness by today’s snowmobile companies to allow their engineers the freedom to innovate. That freedom of innovation has taken us from bogies to slides, leafsprings to A-arms and, perhaps, eventually from one point of braking to three points of braking power.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices