Snowmobile CVT Drives

The simply sophisticated CVT

We look at modern snowmobiles and think how high-tech they are. They come with digitized ignitions, electronic oil pumps, multiple-stage electronically controlled exhaust valves, and turbochargers with compact onboard computer systems that use pre-programmed memory maps to adjust ignition timing, fuel delivery and turbo boost. Some sleds have electric power steering and even computerized externally controlled exhaust systems. These snowmobiles certainly exude the latest in technologies.

Still, though, snowmobile constantly variable transmission drive systems have and haven’t changed dramatically since the dawn of drive and driven clutching where one was rpm-sensing and the other worked with torque loads. While the simple drive and driven pulleys were enough for early snowmobiles, performance needs accelerated the design and sophistication of this seemingly simple system. By the mid-1980s Polaris’ P-85 drive clutch was the go-to clutch for its racing and performance sleds. While Polaris may have partnered with TEAM Industries on modern secondary clutch designs, the P85 remains the heritage drive for Polaris performance, although its evolved significantly since it was introduced.

Even the original Edgar Hetteen created Trail Cat used a CVT to transition the Briggs & Stratton’s modest power to the track.

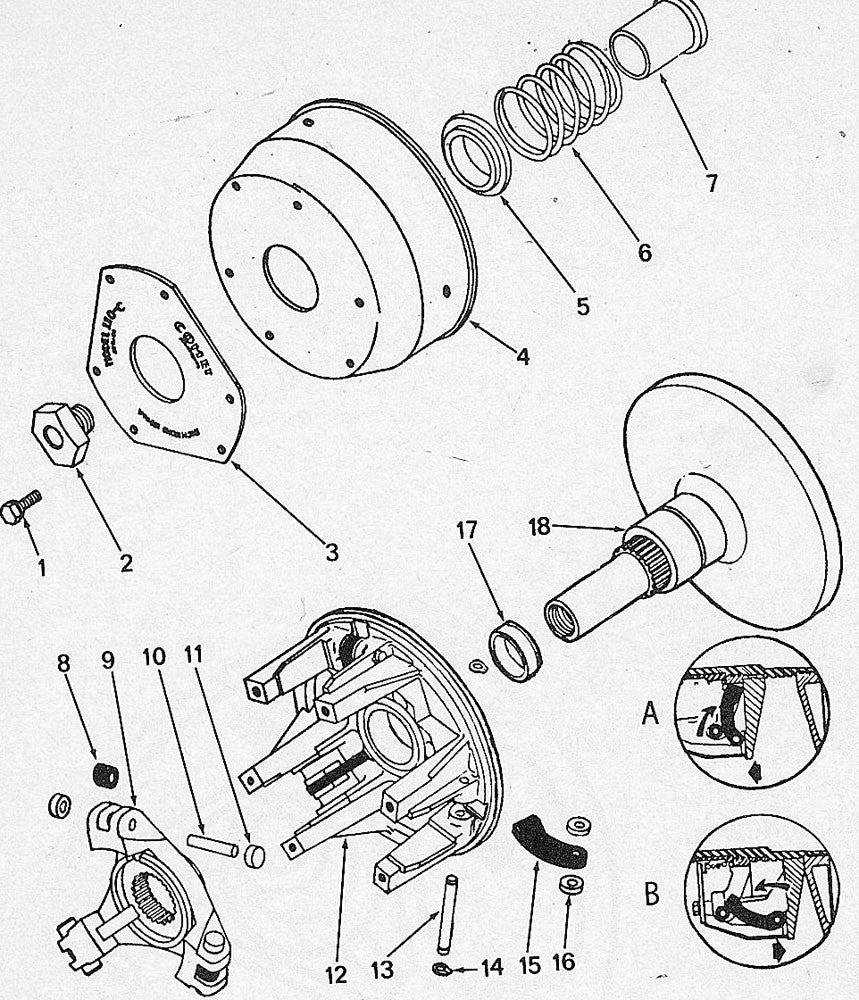

Looking back in our archives we see the names of defunct snowmobile brands with an assortment of drive clutch systems. Ariens, Northway and Skiroule brands included Precico drive clutches on some models. This Drummondville, Quebec clutch manufacturer’s Model 5000 cam-actuated drive pulley featured steel cables to control centrifugal weights and cam movement. In those early days, many clutch makers offered two levels of clutch designs. St. Lawrence Manufacturing Company of Limoilou, Quebec supplied a Standard Duty clutch for up to 22 horsepower and the Heavy Duty version for 24 hp and up. The designed top engine speed for the St. Lawrence drive was 6000 rpm.

One of the early choices for performance clutching came from Los Angeles based Salsbury Corporation, which introduced its “R” Series racing drive clutches in 1970. It was Salsbury’s contention that lower powered snowmobiles were fine with speed sensing type drives when paired with its torque-sensing driven sheave torque converter. The speed sensing clutch worked well with the lower powered sleds that relied on engine compression for some braking, but Salsbury found that its torque sensing system worked extremely well in high performance snowmobiling where quick shifting was important to overcome varying speed and power loss when transitioning snow conditions.

Comet was another pioneer in the performance arena, developing its Model 94C and 102C clutches for use on John Deere snowmobiles. Founded in 1949 by the Hoff Brothers, the company went out of business in 2009 with select assets acquired by Certified Parts Corporation of Janesville, Wis. In its heyday Comet was a leader with its Model 94C Duster series used in low to moderately powered sleds of 40 hp or less and its 100 series units famous for powering winning race sleds.

In its heyday Comet was a leader with its Model 94C Duster series used in low to moderately powered sleds of 40 hp or less and its 100 series units famous for powering winning race sleds.

With the downturn in snowmobile manufacturers to today’s four and overall sales shrinkage, aftermarket clutch manufacturers faded. Ski-Doo pairs its own designs with its exclusive Rotax engines. Yamaha uses its own proprietary design and both Polaris and Arctic Cat work with TEAM Industries on clutching. Polaris has tended to work with TEAM on its driven clutching while Arctic Cat partners with TEAM for both drive and driven units, although Cat favors its own designs for its moderately powered sleds.

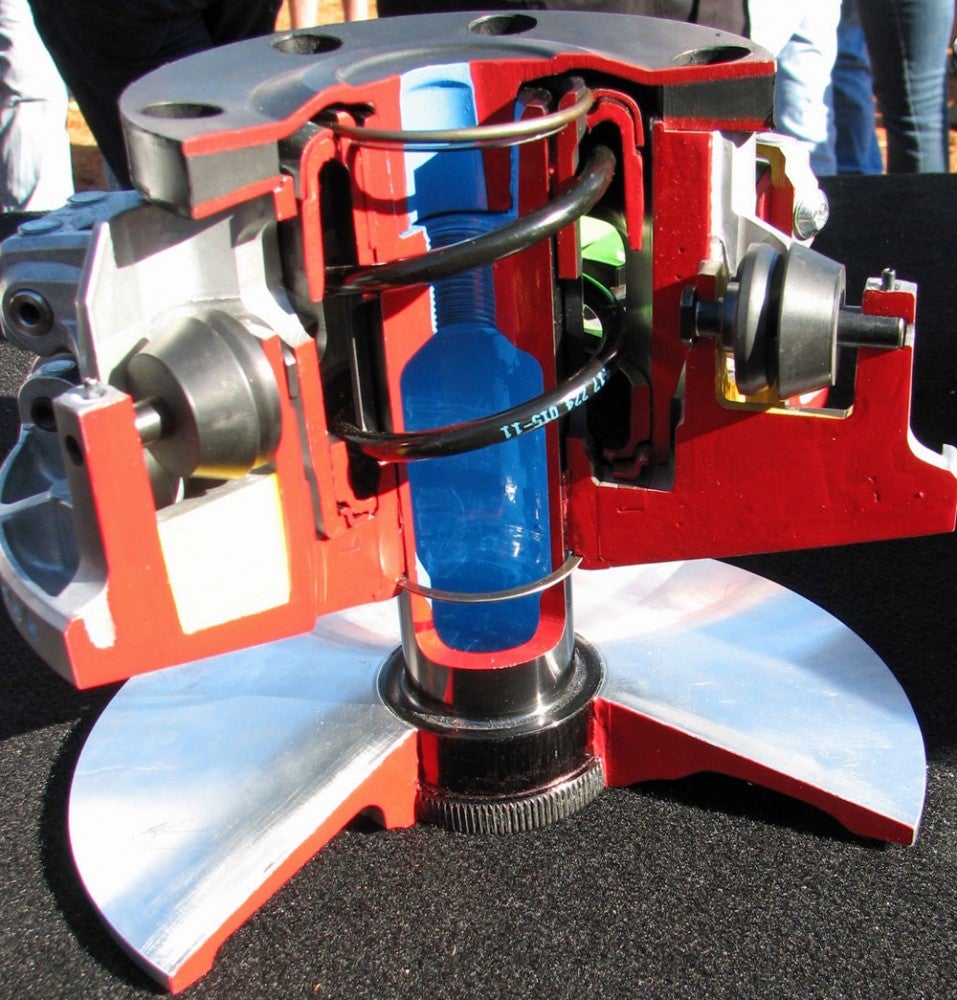

So far we have yet to see a computerized snowmobile drive system, but let’s not bet against it. A snowmobile drive system is incredibly simple. As Comet technicians explained: “The drive clutch is activated by centrifugal force from the engine crankshaft. The movable sheave of the clutch is forced in as the RPM of the engine is increased. This contacts the drive belt. The drive belt will then be forced to a larger diameter within the clutch sheaves, thus pulling it to a smaller diameter within the driven unit sheaves. The movable sheave of the driven unit is forced out, allowing the belt to seek its smaller, high speed ratio diameter. As this happens, the speed from the engine transferred to the final drive is increased.”

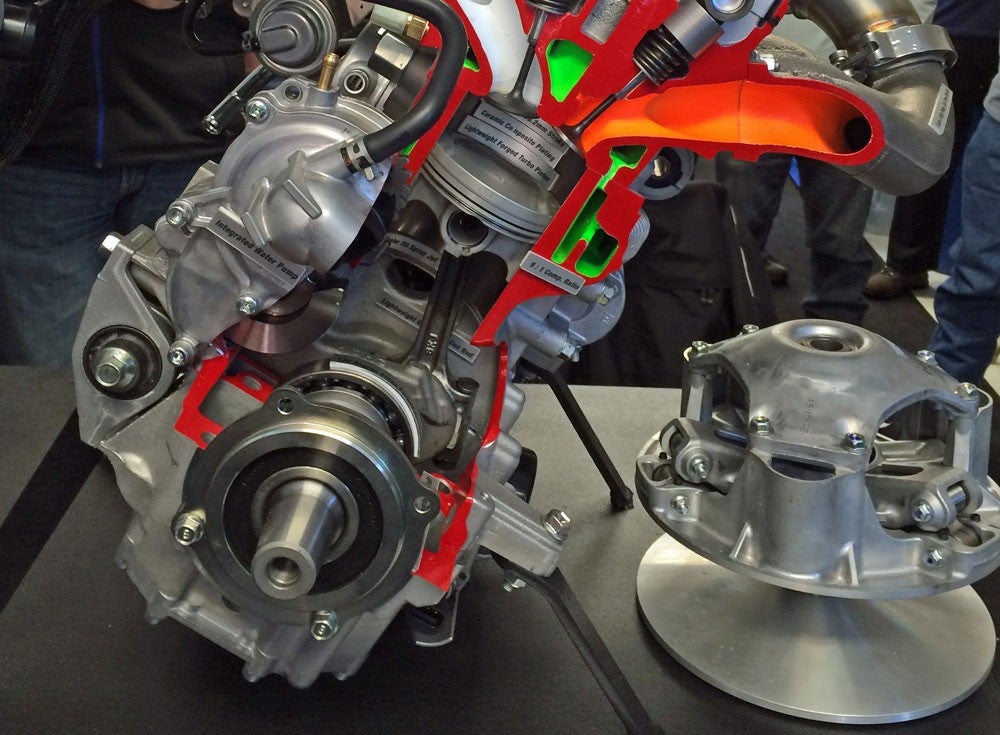

Yamaha revised its drive system to accommodate the reported 200 hp of its new turbocharged one-liter snowmobile engine.

Over the decades, snowmobile drivetrain engineers have finessed this basic system – and they haven’t stopped tweaking it to this day! The drive system of a modern snowmobile owes much to racing, as this proves the adage that racing improves the breed.

When sleds like the 1960s Ski-Doo Olympiques relied on hopped up 10- and 14-horsepower single cylinder Rotax two-strokes, drive systems remained pretty basic. But as power increased and winning races at Eagle River’s World Championship Derby or the Winnipeg-to-St. Paul 500 became ever more important, clutch designs began to evolve from simple ramps with weights to rollers and cam angles. Achieving a bit of overdrive for cross country racing helped and managing effective belt grip became important. Of course, as clutching became more efficient, drive belts had to evolve to withstand the added heat and friction that high performance placed on the drive system.

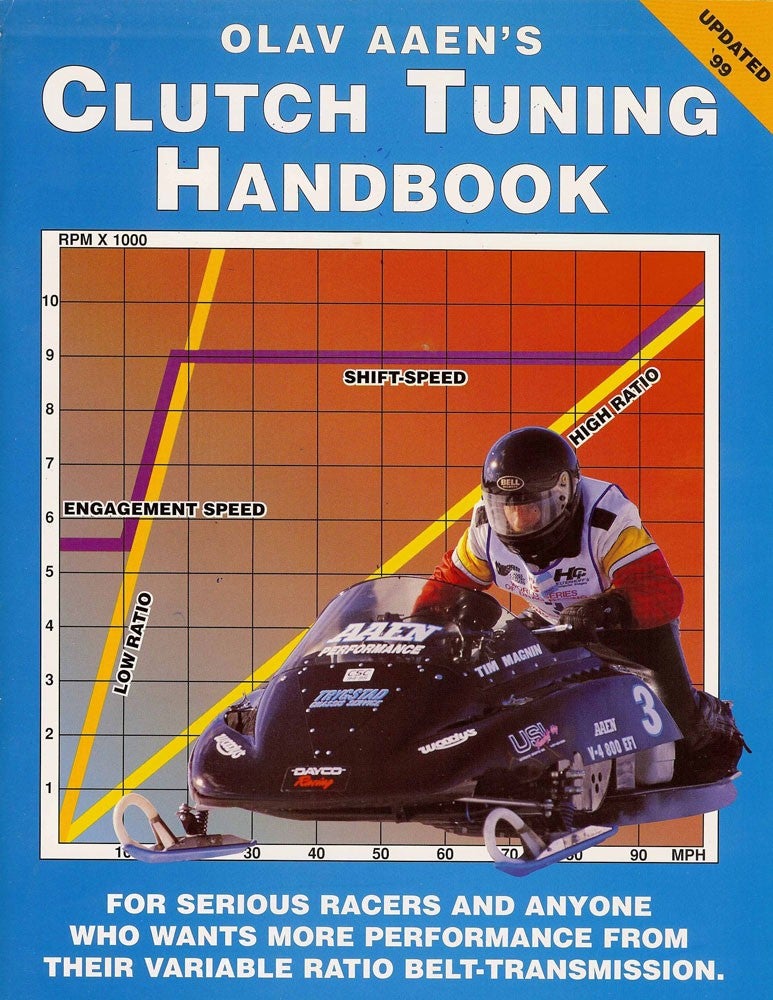

As many snowmobilers strived to exact more power from their stock engines, knowing how to exact matching drive train performance became a “black art” that still breeds legions of aftermarket specialists. One such aftermarket pioneer, Olav Aaen, recognized this specialty and wrote the early bible on clutch tuning in the mid-1980s. His “Clutch Tuning Handbook” remains a must read for vintage snowmobilers.

Olav Aaen wrote the early bible on clutch tuning in the mid-1980s and his “Clutch Tuning Handbook” remains a must read for vintage snowmobilers.

While the nuances of drivetrain delivery have evolved, the basic premise remains. Regardless of whether your sled’s engine is carbureted or electronically fuel injected, the fact remains that to get the best performance, you need a system that allows the engine to deliver performance at its most powerful and efficient setting. This engine sweet spot is the peak of the power curve. Motorcycles and automobiles use multispeed gearboxes to try and maintain efficient revs. That’s why you find some automakers using new eight- or nine-speed transmissions. Some makers decided that the constantly variable transmission had efficiencies for small cars. In the days of snowmobiling, the CVT became the drive system of choice as it could hold an engine closest to its sweet spot.

The modern snowmobile belt transmission can be fine-tuned to provide a constantly changing ratio that keeps the engine in its – and your – happy place! The evolution of the modern multi-ratio cam and roller cam action drive system is nothing more than the sophistication of a very basic and simple system. The nuances of the modern drive require that the engine and clutch system provide smooth drive off for select models and, perhaps, as with the Ski-Doo MXZ 850, a harder hit at midrange to impress a performance rider. Never underestimate the roll emotion plays in snowmobiling. Smoothness is for touring and cruising. Snappy and quick hits play better with action riders. It’s all in the clutching.

The nuances of a modern drive require that the engine and clutch system provide smooth drive off for select models and, perhaps, as with the Ski-Doo MXZ 850 race clutch derived unit offer harder hit at midrange to impress performance riders.

If you want to revert to the old days, check out the rather basic clutching of the Polaris 550 Indy with its paired CVTech Powerbloc 50 drive and Invance driven. That system has a direct pedigree to a design that was offered by Securistat in the 1970s as a stand-alone clutch to pair with most any driven clutch of the day. Incredibly easy to tune, it was designed with weight blocks that accommodated a variety of easily installed weight discs. It is a great alternative clutch for vintage sleds.

Modern snowmobiling may have its high-tech computerized aspects, but it also retains a simply sophisticated drive system that has yet to be bettered.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices