Five Decades of Evolution in Snowmobiling

Snowmobiling constantly evolves. Perhaps not as quickly as in the early days when there were 20 to 30 serious competitors, all attempting to set themselves apart from the crowd. Most likely they were trying to set themselves apart from the market leader, Ski-Doo, but not too far as many of these companies tried to incorporate the success of the Quebec-based leader into their own sleds.

Move forward 50 years and the four surviving companies are still setting themselves apart with attempts at innovation that will attract more buyers. If you are a vintage or antique sled collector, then you know firsthand how far the snowmobile industry has come. And not come!

In those earliest days of the sport, industry analysts predicted annual sled sales of one million units per season. That was more than 50 years ago and those predictions ceased almost as soon as they had been published. Today’s snowmobile manufacturers would be ecstatic to see a quarter of that projection. Last year sales reached a high mark of 150,713 units sold worldwide.

One thing that has not changed is how the sport hands down a tradition of snowmobiling from one generation to the next.

Fifty years ago the thought of owning a 10 percent share of a million-unit sled market could easily justify research and development dollars to set one brand apart from the others. The most aggressive companies looked to racing, especially race wins, to create an image for their sleds. Even though most sleds were sold to trail riders, the concept of a race-winning technology garnered attention. Names like TNT and Blizzard offered more excitement than Trailblazer and such.

The evolution of the snowmobile demanded certain excitement. Arctic Cat’s pioneering slide rail suspension design not only provided a smoother ride, but it could be utilized for racing as well. Were triple belts of track held together by full-width cross cleats better than the same materials used with a three-quarter design cleat system? That was a battle that lasted a couple decades until virtually all sled makers decided that a single rubber track was the best answer for snowmobiles. Until all sled makers adopted that technology, the rubber track versus cleated track arguments marked the ultimate disagreement between Cat, Polaris and Ski-Doo riders. We would imagine that argument still exists within the vintage sled community.

Ski-Doo was the brand that other manufacturers emulated in the 1960s, hoping to steal a piece of Ski-Doo’s leading market share in what was then thought to be an industry with one million annual sled sales.

That’s all ancient history. In reality the track argument simply became compromised. Serious flatland riders may not use steel cleated tracks, but they do use studded rubber tracks. Likewise powder riders switched from the grip of a raised steel cleat to the multi-function grip and give of powder-specific rubber tracks, some with tall three-inch plus lugs that cup and grip the light powder common to backcountry riding. The argument didn’t really go away, it simply evolved to suit riding styles.

In the past 20 years, despite the fact that some snowmobilers and industry followers think change has come slowly, snowmobiles actually have evolved at a surprisingly rapid rate. That’s not to imply that we’ve seen snowmobiles change radically from the earliest days. Modern sleds still feature a common tunnel, or platform if you insist. There is a forward bulkhead. There are two skis. The engines utilize a CVT drive. Those drive arrangements are still mounted forward and have not retreated to the rear of the sled like the early Polaris Sno-Travelers. You can thank Ski-Doo for that modern success, although the original 1924 Eliason power toboggan foreshadowed the snowmobile’s essential configuration.

Although snowmobiling has evolved since the first Eliason power toboggan, it was this sled that foreshadowed the modern sled’s functional lay-out.

With the snowmobile’s configuration established, what could be left for evolution? A great deal! Starting with the 2003 Ski-Doo REV, there was a major change in the rider’s onboard interaction with the snowmobile. In 2016 you won’t find many – if any! – modern snowmobiles with the older style of seating, where you sat way back almost over the rear axle on a low seat with your legs stretched forward. The REV changed all of that by bringing the rider upward and forward to better respond to trail conditions. It paid off for mountain sleds as well, allowing the rider to quickly stand and move in response to cutting into hillsides and such. We would go so far as to state that the REV totally changed the way we all ride. In the backcountry, instead of simply standing upright on the runningboards and wiggling from side to side, modern day riders cut sidehills by using a wrong-footed style that has them with one foot on the runningboard and the outermost leg countering turns.

Of course, while sleds were evolving, they managed to get much heavier. By today’s standards, a 408-pound 2016 Polaris 800 Pro-RMK 155 is a lightweight sled and weighs less than even a fan-cooled Polaris 550 Indy (422 lbs) or a 2016 Ski-Doo MXZ Sport (420 lbs). Of course all those weights pale by comparison to a basic 1965 Ski-Doo Olympique, which weighed in at 250 pounds!

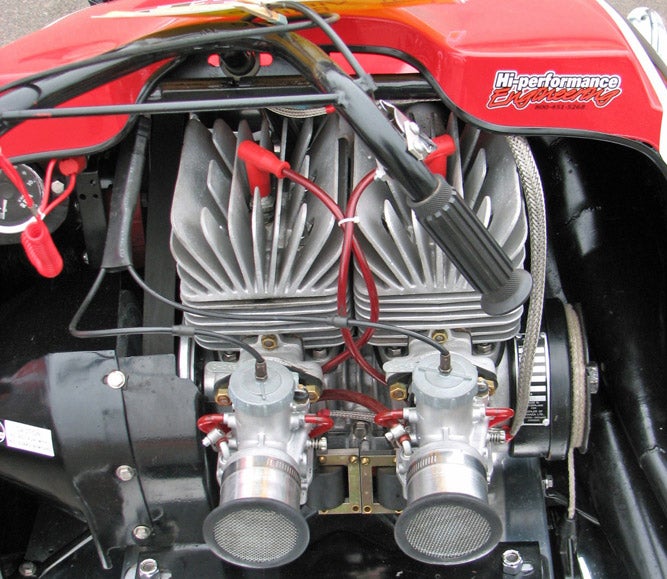

Legislation to reduce engine noise spelled doom for snowmobiles with unencumbered air-cooled engines that could never achieve the proposed standards.

Why was that? In the 1970s the federal government insisted that snowmobiles needed to be quieter, which necessitated bigger and heavier exhausts, actual sound deadening materials in the hoods, baffled intakes and such things. In the early 1970s Outboard Marine Corporation actually managed to create a quiet sled, the company’s Golden Ghost snowmobile managed to get sound levels down to a claimed 73 decibels at a time when the average snowmobile belted out 83 dBa. That’s the difference between being 50 feet away from a diesel truck traveling at 50 mph and normal speech at three feet. Of course, to achieve that reduction, the sled ended up weighing more than 500 pounds.

Lowering sound levels eventually led to liquid-cooling, which is now common in virtually all 2016 models – except for a few 550 fan-cooled holdovers. That evolutionary step also added weight for cooling extrusions, radiators and the new engines.

The quieter engines began an evolution of their own, from two-stroke designs to four-strokes. New intake systems appeared as electronic fuel injection replaced oft recalcitrant carburetors. But this breed of snowmobile engines made everyday riding life easier and more enjoyable. Yes, they proved to be quieter, but more importantly they proved to be more fuel efficient and extremely reliable. New technologies have evolved as well. Ski-Doo proved that its Rotax two-strokes could be almost as clean and efficient as four-strokes thanks to its E-TEC technology, developed for its Evinrude outboard motors. The Rotax four-strokes evolved to provide nearly 30 miles per gallon with the 600 ACE. Multiple modes of engine operation and easy to modulate throttle-by-wire define the newest four-strokes from Ski-Doo/Rotax and in select 2016 Yamaha Genesis engines.

Because today’s modern sled places the rider forward and in better control on the trail, the four sled makers managed to reassess the overall ride and handling. When the REV appeared back in model year 2003, it used a version of the SC10 that was common on the sit back models. The difference was that because you sat forward, centered and more upright, you didn’t endure the bumps as much even though the suspension was basically the same. Eventually the suspension evolved to the rMotion. Likewise, Polaris evolved suspension design to its Pro Ride, Arctic Cat countered with Slide-Action and Yamaha went from Mono Shock to it’s current SingleShot.

Suspensions continue to evolve but it’s unlikely that the sport will return to the telescopic strut design favored by Yamaha in the 1980s. Double A-arm designs seem to be here to stay.

Suspensions should create comfort and confidence in handling. Over the decades snowmobiles have gone from steel skis with leaf springs to long travel double A-arm configurations, with interesting stops in between. That includes Yamaha’s infatuation with its telescopic strut front suspension. Had John Deere stayed in the sled biz, you could have expected a strut suspension from them. As it is, the strut design manages to hold on in select Ski-Doo and Lynx utility sleds.

For more than five decades the sleds of our sport have continuously evolved. We expect that future seasons will continue that evolution, but the type of evolution will also evolve as we now have vastly improved trails on which to ride and deep powder riders utilize modern technologies in clothing and avalanche gear to ride more safely in remote areas of the backcountry. Sometimes it may seem as though change in sleds is s-l-o-w, but if you look at a vintage sled like the 1965 Ski-Doo Olympique, deemed a modern light-footed sled of its time, you can sense the evolutionary upgrades that make up the sleds of 2016 and beyond.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices