Ski-Dooing to the North Pole

40th Anniversary of 1968 Plaisted Expedition

Forty years this past April 20th, a U.S. Air Force weather reconnaissance plane radioed down to a small gathering of men to tell them, “Everywhere from where you are now is south!”

It’s undeniable that the men of the 1968 Plaisted Expedition were the first snowmobilers to ever reach the North Pole. And, they could well be the first men to reach the Pole by land — despite the National Geographic Society’s claim that Robert E. Peary was the first.

The verification of their position meant a great deal to the four men who had spent more than 40 days fighting polar ice to make snowmobiling history. With that radio message the U.S. Air Force verified their historic accomplishment.

The four-men at the North Pole consisted of expedition leader Ralph Plaisted, a 40-year-old St. Paul, Minn. insurance man; navigator and radioman Gerry Pitzl, a 34-year-old university geography teacher; 40-year-old mechanic Walt Pederson, who owned a Ski-Doo dealership in St. Cloud, Minn.; and Jean-Luc Bombardier, the 29-year-old nephew of Ski-Doo inventor J-Armand Bombardier, whose snowmobiles the team rode to the Pole.

Two men not at the North Pole that day, but who played a key role in the expedition’s success, were Dr. Arthur Aufderheide of Duluth, Minn. and Don Powellek, an electronics engineer. They had been flown off the ice and back to base camp to resolve supply and electronics problems that threatened the expedition’s eventual success.

Tight Schedule

According to a 1968 ‘fact sheet’ outlining the expedition’s schedule and equipment list, the non-profit, privately financed Plaisted Polar Expedition members had to leave base camp no later than March 1, 1968 and had until the first week of May to accomplish its mission. This knowledge came from hard-earned, first-hand experience as the expedition’s 1967 attempt was stopped by seasonal storms and ice breakup.

While the on-ice travel was treacherous, the initial travel to base camp proved nearly as grueling. Expedition members departed Minneapolis-St. Paul airport on February 21st for Chicago to board an Air Canada flight to Montreal where they would coordinate with their equipment. Shipped earlier by truck, the equipment passed through customs and on to a Nordair flight to Eureka on Ellsmere Island. Men and supplies were then ferried by bush planes to the Ward Hunt Island base camp on the edge of the Polar Ice Cap. They had about a week to establish their base camp, check out communications, and arrange for supply flights before leaving for the North Pole.

Bar Challenge

Plaisted and Aufderheide must have wondered how a 1963 beer-inspired challenge in a Duluth, Minn. bar had led to their second try to reach the North Pole. The challenge came as Aufderheide, listening to Plaisted boast of the attributes of snowmobiles and tell of plans for a seal hunt in the far northern wilds of Canada, suggested that he expand his adventure to include a snowmobile trip to the North Pole. After all, if Peary did it with dogs, why couldn’t ‘iron dogs’ make it?

The challenge sat for a few years as Plaisted researched Peary’s attempt, which made Plaisted doubt Peary’s claim. After reaching the Pole and spending nearly two months on the ice cap, Plaisted seriously doubted the veracity of Peary’s claim even more.

Years later he told this writer quite simply: “After you’ve been out on the polar ice you know that Peary couldn’t have done it the way he said. There’s no one who could have made it in the time he said he took.”

Slow Going

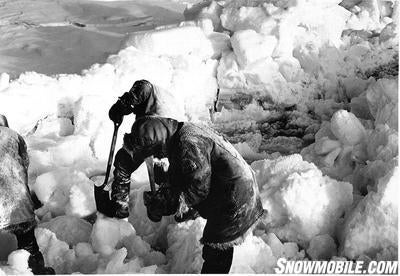

Plaisted pointed to the rigors of arctic travel. He explained that on the best days the expedition made about 65 miles. But these weren’t 65 miles heading straight north. To get around ice ridges as tall as a two-story building the route would veer off course to go around them. If ice ridges couldn’t be skirted, the expedition broke out pick axes and shovels to bridge the ice. Plaisted said that on those days, travel would be limited to only two or three miles.

If you draw a straight line from the base camp at Ward Hunt Island to the North Pole, you total about 425 miles. At the end of the trip, the expedition’s 1968 Ski-Doo odometers registered more than 800 miles to achieve snowmobiling history. Up to seven air drops of fuel and other supplies were flown in to the expedition to keep the riders on the go. It was a tough go as the temperature was consistently -50 to -60 degrees Fahrenheit for the first two weeks and never got above -18 degrees during the trip.

Keeping Warm

Keep in mind that snowmobile clothing of the 1960s couldn’t handle such conditions. Special clothing was found that included an inner parka made of poplin, lined with Sherpa cloth and a hood encircled by wolverine fur.

“This garment would have sent any Eskimo into raptures, and it was only the inner parka,” wrote Charles Karalt, famed CBS-TV correspondent and author of “To The Top Of The World,” a book about the 1967 expedition that he covered firsthand.

Plaisted and his team arranged for custom-made outfits that they tested one night by lying out on one Minnesota’s 10,000 lakes with temperatures dropping down to -35 degrees.

Plaisted recalled being satisfied with the outfits, which cost about US$1,000 each in 1968.

“I was pretty confident you could survive in them. They expelled body moisture so you didn’t build up perspiration inside, but they weren’t any good in a rainstorm because they’d leak,” he confided to us years later.

Quoted in a 1969 snowmobile magazine article, Jean-Luc Bombardier said: “We did many things differently than in 1967… we traveled lighter in 1968… leaving non-essentials behind.” He noted lighter loads made it easier to scale pressure ridges or travel over thin ice.

Moving Ice

Remembering the danger of arctic travel, Plaisted states bluntly, “I was scared the whole time. One time, I remember, we camped in the middle of an ice pan. Anyway, it was night and the ice roared and rumbled. No one said a word. In the morning, navigator Gerry Pitzl went out of the tent first and told us the whole south end of the ice pan was rubble. That’s when our mechanic, Walt Pederson, said, ‘We don’t care what’s going on to the south, we’re going north.’ That’s all that was said about the incident.” By leaving earlier in the year, Plaisted felt his second expedition could reach the Pole within 30 days. He was wrong, it took more than 40 days because of the constantly moving polar ice.

When they reached the North Pole, the temperature was -25 degrees. “It was one of the warmest days we traveled. It was April 19th and we had really pushed hard the last few days because we were afraid the same thing was going to happen that happened the year before when the ice broke up,” Plaisted recalled. “The last two days before reaching the Pole were totally sunlit. The Air Force flew over two or three times and told us we were 40 miles from the Pole.”

“The last 16 miles we finally got lucky and didn’t have to move much,” recalled the first snowmobiler to the North Pole. “We were just coming in on the drift of the ice. We passed over the North Pole at 4 PM on April 19th.”

The US Air Force verified their position at 10AM the next day.

First To The Pole

Plaisted to this day feels that his expedition of snowmobilers was the first to reach the North Pole by land. His accomplishment was unquestionably verified by an outside source. A private endeavor, the Plaisted Polar Expedition didn’t make any scientific breakthroughs. Well, Plaisted does take a bit of pleasure in recalling, “About the only scientific achievement was that we found scotch freezes at -65 degrees.”

Today Ralph Plaisted, who turns 81 years old in September, still maintains a residence north of St. Paul, Minn. He was inducted into the International Snowmobile Hall of Fame in 1990.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices